The Enduring Legacy of Don Quijote de la Mancha: Idealism, Reality, and the Birth of the Modern Novel

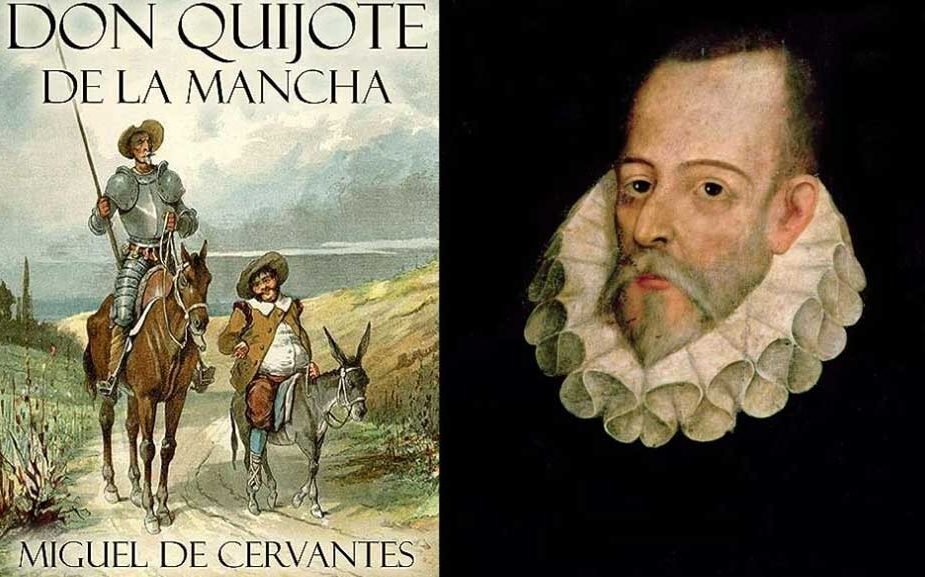

The tale of Don Quijote de la Mancha, written by Miguel de Cervantes in the early 17th century, is much more than a simple joke on the old chivalric romances. It stands as a profound, often hilarious, exploration of the human heart, a deep dive into what we choose to call “reality,” and a cornerstone of the modern novel. The book’s lasting appeal comes from its perfect capture of that timeless struggle: noble, sometimes foolish, idealism against cold, hard pragmatism.

The Mad Gentleman of La Mancha: A Knight-Errant’s Delusion

The Power of Books: From Alonso Quijano to Don Quijote

The central figure starts his journey as Alonso Quijano, a quiet, middle-aged country gentleman in La Mancha. His world shrinks to the pages of his beloved books, where he devours every tale of knights and heroic deeds.

This literary obsession eventually shatters the wall between his reading chair and the world outside. His mind, dried up from sleepless nights and endless fantasy, convinces him that the age of chivalry is not dead, and he must revive it.

He transforms himself into Don Quijote de la Mancha, patching together a rusty suit of armor and naming his old farm horse Rocinante. His self-appointed quest is to roam the Spanish countryside, righting every wrong and dedicating his glory to the imaginary lady of his heart, Dulcinea del Toboso.

The Unlikely Squire: Sancho Panza and the Voice of Reality

Don Quijote’s second adventure brings us his essential partner: Sancho Panza. Sancho is a practical, down-to-earth peasant from the same small village.

He is lured into becoming the knight’s squire by the irresistible promise of becoming a governor of an island. Unlike his master, Sancho is a man of proverbs and simple needs, his feet firmly planted in the soil.

Sancho’s presence creates a wonderful, chaotic balance. He is constantly trying to bridge the gap between Don Quijote’s grand delusions and the messy truth of their surroundings. He is the necessary voice of common sense, yet he, too, finds himself slowly charmed by his master’s vision.

Windmills and Giants: The Conflict Between Ideal and Real

The Quixotic Spirit: Noble Intentions in a Mocking World

The most iconic scenes in the book perfectly showcase the brutal collision between Don Quijote’s noble vision and the world’s indifference. He sees terrifying giants where Sancho can only see the blades of windmills.

He charges a peaceful flock of sheep, convinced they are a hostile army, and mistakes a simple barber’s basin for the legendary Helmet of Mambrino. His pure intentions are almost always met with pain, ridicule, and failure.

This is the very definition of the “quixotic” spirit: a noble, perhaps absurd, commitment to an ideal, regardless of the overwhelming, ordinary reality. Don Quijote’s so-called madness is, in fact, a courageous refusal to accept the world’s limitations.

Incompatible Systems of Morality: Chivalry vs. Pragmatism

Don Quijote attempts to force the long-dead code of chivalry onto a 17th-century world that has moved on. This creates an unbridgeable gap between him and almost everyone he meets.

His absolute faith in enchantment and his rigid adherence to an outdated moral system seem utterly ridiculous to the rational people around him, like the local Priest and the Barber.

Yet, Cervantes subtly suggests that the world’s “sanity” is often lacking in virtue. The Duke and Duchess, who invite the knight and squire to their estate only to cruelly mock them, display a heartlessness that makes Don Quijote’s sincere, if delusional, compassion look truly heroic.

A Revolutionary Work: Narrative, Character, and Theme

The First Modern Novel: Narrative Innovation and Self-Reference

Cervantes’ masterpiece is widely celebrated as the first modern novel, largely because of its groundbreaking narrative style. The author playfully blurs the lines of reality, claiming to be merely translating the manuscript of a fictional Moorish historian, Cide Hamete Benengeli.

This self-aware structure, or metafiction, keeps the reader off-balance, constantly asking what is true and what is invented within the story itself. The very form of the novel brilliantly mirrors its central theme of questioning perception.

Beyond Class: The Distinction Between Worth and Social Status

The book also fiercely challenges the common belief that noble birth automatically means noble character. Cervantes highlights the stark difference between social class and true worth.

The peasant Sancho Panza, despite his low standing, is often the wisest, most thoughtful, and most fundamentally good character in the entire book. The aristocratic Duke and Duchess, in sharp contrast, are shown to be petty and unkind.

This radical idea—that a person’s intrinsic worth matters more than their title—was revolutionary for its time. It is a key reason why Don Quijote remains a groundbreaking and deeply influential work of literature.

The Immortal Legacy of Don Quijote

The End of the Quest: Return to Sanity and Death

The knight’s grand adventure eventually comes to a close. After being defeated in a duel by the Scholar Sampson Carrasco, Don Quijote is forced to return to his home village.

He finally renounces his mad visions, regaining his full sanity just before his death. He dies peacefully as Alonso Quijano the Good. This final return to reality is profoundly moving, leaving the reader with the sense that the world is now a little duller without his magnificent delusion.

The Quixotic in Culture: A Universal Symbol of Idealism

The character of Don Quijote has long since escaped the pages of the novel to become a universal icon. To be “quixotic” is to be an idealist, a dreamer who fights for a noble cause against impossible odds.

His legacy is not defined by his failures, but by his courageous insistence on the power of the imagination over the mundane. The novel is a timeless reminder that the greatest heroism often lies in simply daring to dream of a better, more beautiful world.